History:

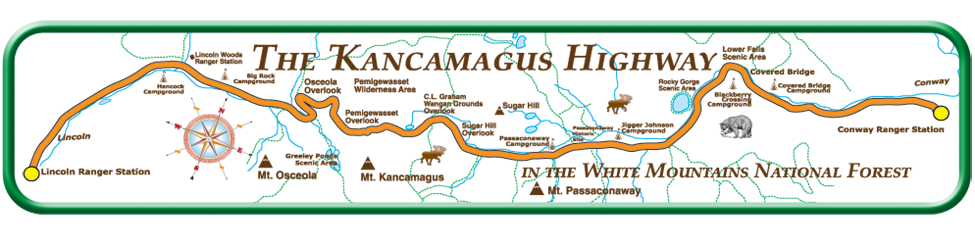

The Kancamagus Highway started as two small roads. One in Lincoln and the other in Conway, New Hampshire.

These two roads were connected in 1959 after years of construction.

The Kancamagus passes through the heart of the White Mountains, filled with scenic vista's and attractions. The road meanders through a vast boreal forest for 34 miles. The Kancamagus Highway has been designated a National Scenic Byway by the United States Department of Transportation.

This site is not affiliated with the White Mountain National Forest.

Kancamagus:

The highway is named after Kancamagus (The Fearless One) a Native American who ruled the Sagamon people.

By DANA BENNER: Correspondent

Kancamagus was one of the most notable leaders of the Pennacook People.

Kancamagus, whose name means “The Fearless One,” was known to the English settlers by his English name, John Hogkin (or Hawkins), and was probably the most feared of all the Pennacook leaders. He’s also one of the least written about.

Students of 17th-century New England history are well aware of Pennacook leaders Passaconaway and Wanalancet, probably because these two leaders remained friendly – or at least lived peacefully – with the English.

Both of these leaders firmly believed diplomacy was the only way to survive. They also believed the English would honor the agreements made with the Pennacook and other native nations.

Kancamagus was of a different mind. He didn’t believe in the words of the English and he felt it was better to fight to keep the land that the Creator had given them. It would later be found that neither way would keep the ever enlarging English population from taking what they wanted. Kancamagus was the grandson of Passaconaway, the son of his eldest son, Nanamacomuck. The English described Kancamagus as “cunning and revengeful” (John Pendergast, “Life Along the Merrimac”). One thing is for certain: Kancamagus hated the English. As a child, he saw both his father and Wanalancet imprisoned by the English. Add to this the numerous injustices done to his people, such as:

- 1.) Unfair and even downright criminal trade practices by English merchants.

- 2.) Native People weren’t allowed to travel in certain areas without written permission

- from the English.

- 3.) More and more land was seized from the Indians for as little as a peck of corn

- annually.

One can understand this hatred toward the English/British.

At the time of King Phillip’s War in 1675, the Pennacook Confederacy was under the leadership of Wanalancet. This was a tense time in Indian-English relations, and Wanalancet tried to keep his people neutral, just as Passaconaway had done 40 years before.

When the war broke out, Wanalancet led most of his people to remote areas where they would be less vulnerable to attack and to limit contact with the encroaching English. In 1674, the township of Dunstable (Nashua) was established by rather dubious means, and Kancamagus, now living among the Pennacook farther north, took this as a blatant affront to previous agreements between the English and the Pennacook.

The only members of the Pennacook Confederacy who took an active role in the fighting were the Nashua and the Wachusett. Although not confirmed, it’s a good bet to say Kancamagus took part in raids on the English settlements in southern New Hampshire during this time. By the summer of 1676, Phillip’s alliance was breaking up, and Phillip was a hunted man. Many of the nations that took up arms with Phillip were fleeing north toward Canada. Some of these nations joined with the Pennacook in the Lake Winnipesaukee area, others settled with the Penobscot in Maine and still others joined with the Abenaki of Vermont and Canada. At the end of the war, Wanalancet returned, with those of the Pennacook who wished to return, to his home on the Merrimack River. Upon his arrival, he made a treaty of friendship with the English. Despite the treaty, the English continued to hunt down Indians who took part, or were believed to have taken part, in the war. Many of these Indians were living among the peaceful Pennacook, Ossipee and Pigwacket. The English considered the harboring of these people an act of war. In the midst of peaceful negotiations with the Nashua nation in the fall of 1676, in the town of Dover, which at the time was called Concheco, Major Richard Waldron attacked the Nashua village, killing 200 and enslaving many more. Those who escaped fled to the Pennacook villages. A second expedition in November 1676, led by Capt. Samuel Mosely, struck the nearby Pennacook villages, only to find them deserted. The English destroyed all they could find and burned the villages to the ground. Around this same time, the English launched an unprovoked attack against the Ossipee, which pulled the Penobscot and Kennebec into the fighting. Because of the violations of the treaty, Wanalancet once again led his people north, this time to St. Francis in Canada. Not all of the Pennacook left with Wanalancet. A war faction under the leadership of Kancamagus remained behind and fought the English militia. Under the leadership of Kancamagus, the Pennacook soon became a formidable force. Their numbers continued to increase as Native People from southern New England continued to flee north. In 1684, the Pennacook presence was being felt and feared by the English setters of New Hampshire. Raids in Dunstable and Tyngsborough were a constant threat. While Kancamagus might not have actively participated in some of these raids, he was surely a mastermind in their planning.

A plan was soon made by then-Gov. Edward Cranfield to enlist the aid of the Mohawk, traditional enemies of the Abenaki and English allies, to dislodge the Pennacook population. With the threat of Mohawk attack ever present, Kancamagus had his people harvest their corn crop and head north to the safety of the area around Lake Winnipesaukee and Lake Ossipee. Kancamagus, in numerous letters to Cranfield, tried to make peace. If the governor had entertained these requests more seriously, a great deal of trouble and bloodshed might have been avoided. On June 27, 1684, Kancamagus and his warriors joined forces with the Saco and attacked Concheco. The warriors quickly rushed and overwhelmed Waldron’s garrison, killing Waldron, burning the house to the ground and either killing or taking captive the rest of the Waldron family. These captives were taken to Canada and turned over to the French. Many were later released back to the English.

The attack resulted in 23 English being killed, 29 captured and five or six homes being burned. The Indians had fled with their prisoners before any resistance could be put together. The attack was well planned and executed, showing Kancamagus’ skill as a tactician and leader. Afterward, the General Court of Massachusetts labeled Kancamagus an outlaw and put a price on his head. A group of English militia under the command of a Capt. Noyes was sent after the Pennacook raiders, but Kancamagus had retreated north to the upper Androscoggin Valley. By the time Noyes had reached the last known village, it had already been deserted. Another party, this one led by Capt. John Wincot, marched north to Lake Winnepesaukee, where, according to Cotton Mather, “They kill’d one or two of the monsters they hunted for, and cut down their corn.” Despite these operations by the English, Kancamagus remained in the area and soon launched an attack on the settlement at Oyster River. Finding the Merrimack Valley unsafe for the Pennacook, Kancamagus brought his people to the sources of the Saco and Androscoggin rivers, where he joined forces with other bands of Abenaki Peoples. From here, Kancamagus and other Abenaki leaders launched attacks against English settlements in New Hampshire and Maine. In September 1690, an English force under the command of Capt. Benjamin Church located and attacked Kancamagus’ village on the Androscoggin River. Somehow, Kancamagus was able to escape the attack, but his family wasn’t so lucky. His sister was slain and his brother-in-law, wife and children were taken captive, although his brother-in-law was later able to escape. Church took the captives to Wells, Maine, where they were used to lure Kancamagus to the peace table.

In response to the attack on his village and the capture of his family, Kancamagus launched an attack on Church at Casco, Maine, on Sept. 21. After a great deal of hard fighting, which resulted in the death of seven of Church’s men and 24 wounded, Kancamagus was beaten back. With the English still holding his family hostage, Kancamagus was forced to make peace with the English at Wells. With his agreement of peace, Kanacamagus was reunited with his family. After 1692, little is written about Kancamagus. It’s possible that once he recovered his family, he continued to fight alongside other Abenaki people, although that is purely speculation.

Keep in mind that all this turmoil was during ENGLANDS (The British) occupation of New England.

Dana Benner, who grew up in Hudson and lives in Bedford, is of Penobscot/Micmac descent and is a member of the New Hampshire Inter-tribal Council. He has been studying and researching Native American history and culture for more than 25 years. His research has taken him throughout the Northeast, Alaska, the Plains and Hawaii. He has given seminars to schools and civic groups on the Native history of New Hampshire. He is also working toward a Bachelor of Arts in U.S. History and Native Culture from Granite State College.

Russell-Colbath Homestead:

TheRussell Colbath Homesteadoffers a

glimpse into the life on a homestead and provides a sense of the struggle for survival and settlement in this remote mountain valley.

A homestead typically consisted of a rustic dwelling, a small garden, and a barn for livestock.

The Russell-Colbath Homestead is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The house is a wooden frame dwelling constructed between 1831 and 1832 by Thomas Russell and his son, Amzi.